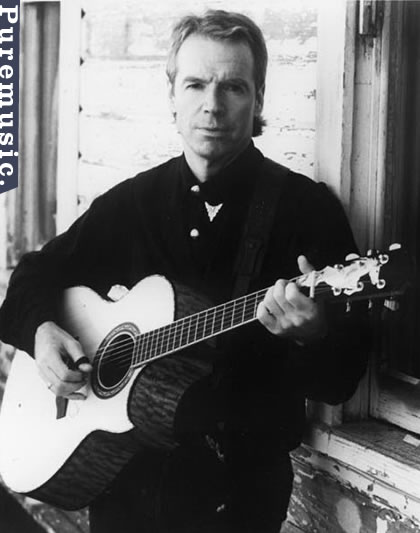

A Conversation with Danny O'Keefe (continued)

DO: Another one of those great stories -- glad that I have them.

I was signed to Dylan's publishing company, Special Rider Music, by Tom Snow's daughter -- Tom Snow, a great songwriter -- Tina Snow. She had taken a song of Dylan's -- it might have been "Forever Young" -- I can't remember what the song was -- and she demoed it with somebody else, so it didn't sound like Dylan. It sounded like the OJs or something. I'm not sure if she did it on her own or how it worked, but I think she was a friend of Carol Childs who was also a friend of Dylan's. And they gave him the tape or -- somehow they met -- I think they may have even got it cut, right? And then all of a sudden the people there realized, "We have a whole catalog, the only thing that keeps people from cutting these songs is that they can't do them like Dylan. So let's demo them so they sound like demos. They're great songs. Let's rearrange them." It's a great idea. There's a huge catalog there of coverable songs.

So out of that she said, "Well, I'd like to think about signing writers." And I was the first writer. "All right. Great." They were very fair to me. I really loved working with them. So one day Bob sends a demo tape -- I'm not sure if it was something from the -- what was the band with George and Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty and -- who was that other guy -- the former Sun artist?

PM: [laughs]

DO: Yeah. What an amazing band that could not have been imagined except by the people who were in it. And Bob sends me an instrumental demo. It's like, "Wha? Huh?" And there's nothing much in it, it's bare bones.

PM: There's no melody indicated --

DO: No, not really.

PM: -- it's just a track.

DO: Yeah, there are some chord changes, but there's not a lot of that. And at one point you hear a voice off the microphone say, "Well, well," and they go to the change. Right? But it doesn't have like regular verse respect chorus, anything, it's just that. It's like an interruption of a band.

So I know I'm never going to get another shot at a co-write if I don't make some magic here. I mean, I just sort of took it as a joke in a way. And I just took that "Well, well" and I added another "well." You know, "You heard about three holes in the ground, didn't ya?" And I made it a song about ground water. Right? What bigger issue do we face, particularly in the West, but in the world as a whole. Ground water is going to be a lot more expensive than oil or gold or platinum or diamonds. I mean, you'll beg somebody for a five-dollar pint of water at some point.

That's basically it -- I sat and figured out a good pattern for it that had interesting chords, and gave them a demo and I sent it back. I sent Lindley a demo somehow, and I can't remember how that happened. I just sent him a tape of songs I had, and he jumped on that one. It fit into his style. I never heard from Bob's company, never heard from Bob. No one ever said that they think it was a good song or anything.

PM: Nothing?

DO: Nothing.

PM: Nothing! I mean, it's great, all the great things that happened to that song, but that just sucks that there was absolutely no communication from the... When it began with them sending an instrumental version, I mean, it's like, "Come on, you started this."

DO: But I thought it was perfect. I mean, it was the continuation of the enigma. The demo was enigmatic, and the reply was, of course, expected, and enigmatic.

PM: The perfect punch line to the riddle.

DO: Yeah, yeah. It was good. And I hope someday that he gets to someplace where he cuts it. But I don't have any real anticipation of that happening.

PM: Yeah, I mean, one wonders, does he have any recollection of the song. Did he ever even hear what came about?

DO: Oh, he knows about it, because I think he and Maria talked about it.

PM: Oh, great. So you know that at least.

DO: Yeah. I think he's well aware of it, he's just having his fun.

[laughter]

PM: I'm enjoying his current reinvention of himself.

DO: The history of our artists, regardless of who you're talking about, whether it's Walt Whitman or T.S. Eliot or anybody you want to talk about, he has a unique place that will hold itself through time. He will be someone who is referred to as having been important.

PM: Absolutely.

DO: And that's a very special thing. There's a body of work that when you finely digest it and decide which are the ripe apples and which are the ones that you're not going to keep, there's still going to be a lot of material there that will hold itself.

PM: And Jesse Colin Young is an old friend that you wrote some songs with, right?

DO: Yeah. Still a good friend. I don't see him much because he lives in Hawaii. But I communicate with him, don't necessarily talk to him. But yeah, an old dear friend. I love him.

PM: We might touch upon him again in the coffee part of our conversation. [Jesse has an organic coffee farm in Hawaii -- find out more about it here.]

You've known in your time and toured with so many cultural luminaries. Who among them are still close friends, some of the -- all the big names you've gigged with and toured with, who, when it all trickles down are like, "Oh, yeah, I'm still tight with them" -- because you know how those things come and go.

DO: Jackson and Bonnie. They were dear friends before we ever played, or before I ever played, opened for them, or was on the road with them or whatever. We did benefits. But I knew them -- Jackson was the first artist that David Geffen was going to sign to a label that had not had a name or funding. But Jackson was his first artist. And so that album that is really just called Jackson Browne, but which is always referred to as "Saturate Before Using" has always been a funny idea -- so I heard that in its demo form, and I thought was very good. I always remember I particularly liked "Song For Adam," which I still think is a great song. I think Bonnie and I worked together at the Troubadour, which is where I met her. And gosh, she worked for Warner Brothers, so everybody was kind of in the same family. I knew Lowell, and everybody was friends with Lowell. We all kind of knew each other.

PM: He must have been a very unusual kingpin on the scene.

DO: He was great. Lowell was a lot of fun. I'm sorry I didn't write with him. I mean, I know now how to write with people, but in that early period, I really only wrote by myself in sort of my own strange convoluted way, and I didn't really understand that and all the reciprocity that you need in collaboration. There were a lot of people -- I mean, I wish I'd written with Donny Hathaway. I wish I'd written with Hall & Oates. All the people who were open to that, I just didn't have a clue.

PM: How did you interact with Hall & Oates?

DO: Arif was recording them. They were doing Abandoned Luncheonette in Atlantic Studio. At the same time Bette Midler was in there cutting a record.

PM: And they were open to co-write and--

DO: Oh, yeah, they wanted to write. It's like I'm too thick.

PM: "I don't do that," yeah.

DO: I didn't actually understand how to do it. That was a skill that I learned from doing a few ads. I finally realized that there is a systems approach that one can take so the creative process doesn't have to always be this blind stumbling through the dark.

PM: When did you start to co-write, to have the first positive co-write experiences that led you to the understanding of that systems approach, for instance?

DO: Right. I think it's with Bill Braun. I don't think I knew that he was a keyboard player. And he had a synthesizer, and he had these bits and pieces. I can't remember what the first song that I would have written... that would be interesting. I'll have to go back and research that.

PM: Because it's such a milestone, the first song that really works with somebody, that isn't just a diluted version of what you started with, it was something that happened.

DO: Right. I think it's on the first -- after I left Warner Brothers, it was a mutual agreement, they kind of didn't know what to do with me, I didn't know what to do with me. And I'd made a record called The Global Blues that nobody had a clue...

PM: Was it a political record? What was it, The Global Blues?

DO: Well, no. I mean, it is kind of a pastiche in some ways, unfortunately, because it has all those -- again, those influences, there are country influences as well as jazz.

PM: Ah, yeah.

DO: I mean, Tony Williams plays on it.

PM: Wild!

DO: Yeah. Roger Calloway plays on it. I mean, there are some really interesting things on it. It was a lesson, in a sense, that in those days -- I mean, we had a budget of $125,000. I'd give a digit -- not a finger, but a digit for a budget of $125,000 in this music business, the state of it is today. If we had stopped at $75,000, we had some rawness in it that was very attractive, kind of those board mixes, the first stuff that comes off and you go, "Mmmm, we got some muscle in that." But then part of the problem of having enough paint and canvas is that you just keep throwing paint there.

You know that movie of Picasso, where it's in two halves. And in the first half he's using emotions behind a screen, and he's just sitting there in his shorts and just painting with these ink -- emotion. But then the second half of it he's actually doing the painting. And it goes in stages. And in that painting there are at least five exquisite Picassos, right? Just gorgeous. And in the end, he finishes it, and it looks just like a Picasso. But he says, "I put too much paint on it. I ruined it." I'm not saying that I had a Picasso, I'm not trying to imply that. But I put too much paint on it.

PM: Yeah.

DO: And that's part of the thing that you have to learn is that sometimes the bones are more interesting than all the flesh.

PM: Yeah, much less the makeup, right.

DO: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Sometimes just a champion pig is what you want to look at. You don't need all that lipstick and rouge.

PM: [laughs] And along the way, I was surprised to find there were no less than ten records in your discography. Six in the '70s, two in the '80s?

DO: Six?

PM: Yeah. There's Danny O'Keefe, right?

DO: And then O'Keefe. Then Breezy Stories, Harry Truman, American Roulette, and Global Blues.

PM: Yeah.

DO: I'm amazed.

PM: And then The Day to Day is '80s.

DO: That was the joke. They didn't want to put it out as The Day To Day, so I said, "Well, let's just call it Redux." And then Running From the Devil [released in 2000].

PM: And so in the '90s you were doing something else.

DO: Yeah. I mean, in the '90s I wrote for Dylan's company. I wrote for a company here for a year called Bluewater Music.

PM: Oh, you wrote for Bluewater?

DO: Largely based on Bonita Allen signing me. I loved her. I thought she was a really good appreciator of songs. I still think she is.

PM: And were you writing whatever you chose to write? Were you writing for the country market, or what were you doing?

DO: To be honest with you, I don't think I ever understood how to write for the country market.

PM: Right.

DO: I wouldn't understand how do it now. But I was writing with other people.

PM: Were you writing with Jim Lauderdale or Al Anderson or those kind of guys?

DO: No, I didn't write with those guys. Those guys were Bluewater writers, and I didn't write with them, for whatever reason, I think just because Lauderdale and I just didn't have a chance to get together. We talked. We met.

PM: He's a hoot.

DO: Yeah, I liked him. I still like him. I just wasn't here. I mean, I just would come for two weeks and furiously work with whoever. I liked writing with Vince Melamed, Fred Knobloch -- and oh, a bunch of different people. A lot of it isn't country. It has to be what's moving. I don't look at the charts. If it works out that it's a song that somebody can cut and maybe even rearrange to their taste, great, go ahead on. I mean, my favorite version of "Good Time Charlie" is Waylon Jennings.

PM: That was a great version. I heard that this morning.

DO: He just plays it like Waylon. Right? It's a Waylon record.

PM: Totally different groove.

DO: Yeah. I mean, that's how I thought that it ought to be. I remember somebody calling me up -- it was on like Midnight Special or one of those shows, and somebody from the East Coast called me up and said, "Be sure and watch this, because Waylon just sang your song."

PM: Sang the hell out of it.

DO: Yeah. I thought it was great. And that's how I got to know him. He was playing someplace, the Palomino or someplace in L.A., and I just went out to see him to thank him. I didn't see him enough after that, but he was a friend for that brief period of time.

PM: Wow. And so what was it like meeting him?

DO: He was great. He was absolutely regular, a regular human being. Probably took a little bit too much uplift, but he was a great guy.

PM: [laughs] Yeah, I heard he did. continue

print (pdf) listen to clips puremusic home